Chapter 3 Neuengamme

Our journey was long. Our bones aching from sitting. Around noon on the third day we arrived at a small station near Hamburg called Neuengamme. We got surrounded by young punks from the SS of around seventeen - eighteen years old. Of course, with rifles, bayonets and dogs. After an hour’s march we came to a concrete square. Around us, miserable barracks, and next to them even more miserable human skeletons. Between the barracks wire-fences, probably to prevent making contact with each other. After Auschwitz, the camp seemed to us at that time as a camp-site. The terrible state of the local prisoners savouring our horror, that in a few weeks, we’ll look the same.

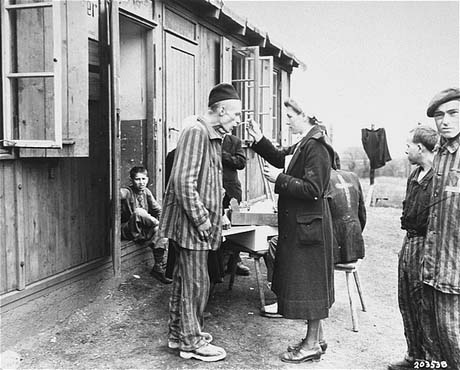

Figure 3.1: A sick Polish survivor in the Hannover-Ahlem subcamp receives medicine from the Red Cross, 11 April 1945

They separated us into blocks. We got the new numbers. I received a number 18 665. Instead of striped pyjamas, we were provided civilian clothes that belonged to those that were killed. On the clothes, a red cross painted with oil paint on the chest and backside. No jews were in the camp, except for those who lived under an faked name. The majority of the prisoners were German politicians (the Communists), otherwise it was a bit of criminals-burglars, and the rest were Poles. This camp already had several branches: Bremen, Varge, Dritte and others. Prisoners from the Neuengamme were often sent to these branches.

A thousand of healthy, reasonably well-looking prisoners, those who already had a unbelievable experience and only saved from death by chance, they revived the camp.

On the third day we were led to a long square, still covered with snow. On the other side of the square was kennel in which there were 50 dogs. On this square, a gun factory had to be built, called Fertigungstelle. Further 500 meters to the east there was a canal, on which boats and tugs were moving, importing sand for the construction of future factories and other construction materials. Next to the canal was a large brick factory.

The construction manager was a tall SS man, Unterscharführer Rese, called by the prisoners Maciejewski. The name was given because, like the cat Maciejewski, he killed people. The function of oberkapa was filled by prisoner Walter Block, a decent German-communist. They divided us into groups. First, we moved earth, then we brought in the materials. I was assigned to a group of moving sand. We carried is by barrows, four persons per barrow. From the canal to the construction site. We were constantly on the move. It was terribly cold - coastal winds pierced the flesh to the bone. Everyone who could, collected some paper from cement bags and put it in the underwear. But pity to him who got caught. He got a beating until it was to painful to watch. However, we were forced to cross the ordinance, as the cold were unbearable, often aggravated by rainy-snow. The effects of the cold soon came to us. On our heads and necks we got ulcers, tormenting us incredibly.

After a so called quarantine period, during which it was forbidden to lay contact with the old inmates of the camp, we got separated under different commandos. I was assigned to Zaunbaukommando. Our kapo was Johann Schmidt, an elderly man, a communist. I got a manageable job in the construction of the fence. We put high poles, similar to Auschwitz. Another group pulled wires and set barbed wires. Several times plans for the fence changed, so that we were also moving poles. The work was prolonged. It was an advantage, since good work was to be respected.

After some time, the political branch began checking our personal data. Letters we sent to all the places of birth and residence, requesting to carefully check the personal data. It turned out that many of us have foreign names. Back came the replies that this or that had long since been dead. They began to call us to the political department. Many persons taken did not return to us. My friend, with whom I worked, gave the name of Dobija. It turned out that his name was Kazimierczak and was a lieutenant in the Polish Army during the interwar period. Not uncovered in Auschwitz until the poor man came here. Leaving Auschwitz he thought of escape, this time he stood at the precipice. What finally happened to him, I do not know, because in the meantime I left the camp.

Autumn of 1943, our working commando was next to a brick factory. Here I met several colleagues from the Messap commando. Mostly they were Poznanians, for example. Miecio Krauze from Wrzesnia, near Poznan. Spychała under Miedzychód and many others places.

At the brickyard there was the Klinkerwerkkommando. It was one of the toughest commandos in the camp. Every day we watched as they were herded, beaten and kicked. Even worse than this Elba commando. Work in this commando finished off mass of prisoners, as they continuously worked in the water.

On Sunday, we also worked at the excavation for the new building. The work was hard everywhere, and hide from it was not possible. The camp at Neuengamme, however, differed substantially from Auschwitz. People here did not die en masse. Occasionally there were hanging, shooting, but not wholesale slaughter. Kapo’s, Vorarbeiters, were recruited mainly from the Communists. The SS may even been worse than Auschwitz, but they had no helpers in finishing off people. Many prisoners went on wires and perished from electrocution.

The commando for the construction of the fence continued through the year with varying degrees of luck. From time to time I received beating with the whip or fist, but not experienced it as bad as in the previous camp.

New victories on the fronts inclined to the side of opponents of the Third Reich. Planes constantly bombed Germany. In July of the same year, raids bombed Hamburg terribly. More frequent alarms wreaked panic among the Germans. Prisoners helped sorting out Hamburg after the raids. They brought all sorts of information about the damage done by the phosphorous bombs, etc. The smoke of the burning city obscured our camp.

At the same time course in the camp had eased a little. Although Lagerführer Mayer got replaced by Lagerführer Thumann from Majdanek, he tightened discipline, but did not managed to turn the camp into an abattoir of people. We went to work normally, but all of us felt that the end of the criminals-reign is imminent.

Beside the brick factory, we set dozens of poles in such a way that it brought cover and rest all day over excavated pits while waiting for the end of the war. One person was standing watch and to alert us if necessary. Then we worked with redoubled energy. It worked successfully for a long time. But the pitcher goes as far until the ear doesn’t tear off. Once, before the end of the work we went in a group and we started to talk about our experiences. Suddenly, unexpectedly arrived the Lagerführer. He wrote the name of the commando and my number as the guardian of the group. Knocked on the whole. It has not helped explaining that we were only gathering for ending the shift and such. It was in April 1944.

On the evening roll, my name was call out and I had to present myself for the whole camp. I was told to bow my head, which got tied to the stool together with my hands. Two of the strongest camp prisoners whipped me more than 25 times over my behind. I saw all the stars in the sky, but gave not even a whimper. The Sturmführer did not enjoyed it and therefor ordered to repeat the portion. Of course, he ordered to lash faster and with more force. This time, I not even felt the pain. My-continued silence brought the Sturmführer into a frenzy of rage. Apparently he did not want to loose face - the called to end the appeal, and I had to be escort the shed next to the kitchen. There, he only changed the executioners. Again, I received my portion. After that, they released be to the block hut.

Please try to imagine, how I moved myself to my hut. Józio Ślaski and Bolek Maciaszek took me under the arms and brought me to the bunk. There they washed off my blood and put compresses on me. For three weeks I could not sit, and I could only sleep on my stomach.